Inspiration: mypy/issues#3186. Please see that issue for a rich discussion and some very useful context and history. It’s long, but worth the time if you care about this issue. This post picks up from that thread.

I think solving this use case I identified in #3186 would go a long way:

I want to publish a library that does math on numeric primitives. I want to provide algorithms. I want my customers to be able to supply their own number implementations. I want to support typing annotations so that my customers can use existing tools to know whether their supplied number primitives satisfy interoperability requirements of my library. I also want to be able to check this at runtime in my library.

High bit: I think it’s important to define and enforce flavors of numerics as generic APIs. Builtin types should be compliant implementations.

At a high level, I think this involves:

- Building something that allows for defining generic numerics and their operations. I’m pretty sure the consensus is that Mypy’s protocols are (currently) insufficient for this purpose.

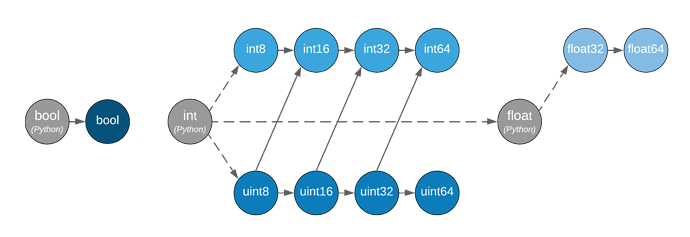

- Replace or simplify the numeric tower to comply with common operations (existing dunder methods seem reasonable). Establish explicit conversion/promotion APIs (both generic flavors and to builtin types). Minimize and explicitly and generically type implicit conversions like with

__truediv__and__pow__. - Bring both implementation and type definitions into compliance for all standard library primitives.

Mapping flavors onto a class hierarchy so far seems problematic, but it may be possible with care. I don’t think a class hierarchy should be a requirement. (I.e., we shouldn’t be afraid to ditch PEP3141.) Well-defined conversion/promotion APIs may suffice as an (albeit potentially complicated) alternative. I think the standard library is in a good position to define at least FloatT, RationalT, IntegerT (and maybe ComplexT), but if it does, builtin types (including Decimal and Fraction) should be compliant and should validate against those APIs.

I think achieving this in the standard library works benefits beyond just enabling generic algorithms to work with compliant numeric implementations. Additionally, it would act as a forcing function for internal consistency between numeric typing and numeric implementations. Further, it could role model techniques for third party math and science packages that promote interoperable extensions.

__truediv__ presents an oddity where an operator involving a single flavor (IntegerT) can result in a different flavor (IntegerT / IntegerT -> RationalT or IntegerT / IntegerT -> FloatT as it is currently). __pow__ presents additional sharp edges (IntegerT ** RationalT -> FloatT). Those and similar cases can probably be accommodated with care. @overloads may end up fairly complicated, but that may be an acceptable price to pay. Having clear lossy-vs-lossless conversion/promotion interfaces will likely help.

I don’t think it’s necessary to require interoperability between numeric implementations, but I think if you solve the above problem, you’ll get a lot of that anyway, especially if you enforce the presence of conversion/promotion interfaces like __float__, __trunc__, __int__, __floor__, __ceil__, etc. (maybe add __numerator__, __denominator__ with a default implementation for IntegerT, etc.). Numeric implementations could rely on Supports… interfaces to type and perform conversions/promotions before performing their operations. Or they could provide their own conversion/promotion implementations (e.g., sympy.sympify, which I believe is called implicitly to allow things like sympy.Symbol("x") + numpy.int64(0) to work). That being said, I think it’s really important that conversion/promotion APIs are clear when those are lossy vs. lossless. (SupportsInt for example is ambiguous. float.__int__ is potentially lossy. numpy.int64.__int__ is not.)